Ask Pip Westwood what she loves most about being a play therapy practitioner and her passion for the role is palpable.

‘It’s the honour of being entrusted with children’s stories,’ she says. ‘Being able to witness, first-hand, a child’s growth and development as they overcome something in their past that seemed so bleak.

‘Each child comes with different strengths and needs, and when you meet them, their heart is on their sleeve.’

Pip works in private practice with two other play therapists under the banner of Wildflower Play Therapy in Adelaide. Since graduating with a Bachelor of Psychology in 2011 and going on to complete a Masters in Child Play Therapy, she has seen the industry slowly grow and gain traction in Australia as a respected and successful form of therapy for working with children.

Play therapy is an evidence-based approach for working with children backed by decades of practice and research, particularly the work of American psychologist, Virginia Axline, in the mid-20th century. Axline developed child-centred play therapy and a set of principles that guide therapists in creating safe, supportive, and non-directive environments where children can explore their feelings, make choices, and develop self-awareness through play.

‘Because of pioneers like Virginia Axline, Garry Landreth and Athena Drewes, everyday I journey into the intimate stories that children choose to share with me through the power of play,’ Pip says. ‘Because play is their number one form of communication, my role as a therapist is to discover, analyse, and unpack their experiences.

‘It’s about giving children the opportunity to be heard in their language. If I’m asked to describe it, it’s like each child comes into the playroom with an itch they need to scratch—a need that’s met within the playroom. They gravitate towards the resources they feel called to.’

Every play therapy room has a diverse range of toys and resources aimed to provide kids with the words to tell their story. Pip often sees children gravitate towards a ‘self-figure’—something they feel connected to and might use to experience their journey.

Like the young boy (who was selective mute) who immediately connected with a dragon puppet in Pip’s play therapy room.

‘This young boy tied up the dragon’s mouth with a piece of rope,’ she remembers. ‘He then chose two little dinosaurs with move-able jaws and made them snap and pinch at the dragon.

‘It was one of those play therapy moments where I could feel the emotional weight of what I was seeing—knew it was significant—but I didn’t have the context to interpret the metaphor being expressed to me.

‘In a review meeting with his mum, she told me there were two children at her son’s school who were pinching and bullying him during class to try and induce him to make sounds. With the help of the dragon, he was playing out the experience of having his mouth almost tied—not being able to speak out.

‘That was such a powerful experience for him. Being able to come in and tell that story, not with words, because he didn’t really speak to me at all, but through play he could communicate the experience he’d had.’

Play therapy is still in early stages of development in Australia—it is much more established overseas, particularly in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. While awareness and interest in the therapeutic benefits of play are growing, Australia still faces challenges, such as limited formal training programs, inconsistent professional recognition, and a lack of widespread integration into mainstream mental health services.

‘In Australia we’re still establishing regulation,’ Pip explains. ‘Regulation around what a child is going through, how to keep them safe, and how to keep us safe as professionals. Theoretical grounding and the right kind of qualifications—all these things are still playing out.

Pip says that while word of mouth is one of the main ways parents come to hear about play therapy, professional referrals continue to increase.

Pip says that while word of mouth is one of the main ways parents come to hear about play therapy, professional referrals continue to increase.

‘We have children referred to us by Child Protection, paediatricians, GPs, and other allied health professionals,’ she says. ‘Schools will often recommend that kids come to see us. There are a growing number of pathways to our door.’

Pip is also a big fan of Innovative Resources’ cards when it comes to helping kids talk about their experiences and feelings, using sets like The Bears and Cars’R’Us in creative and spontaneous ways.

‘I’ll often use The Bears to play a type of charades,’ she says. ‘I’ll choose a card at random, then have the child act out what’s on the card and guess the emotion. It can be a really great way to build emotional intelligence, but also social acumen—understanding how others are feeling and being able to read those really subtle facial expressions.’

Pip also remembers a powerful interaction with a young boy using Cars’R’Us.

‘I was working with a child who had some pretty complex issues in his home life, particularly in relation to parental addiction. I simply asked him to, “choose a card that tells me how you’re feeling”.

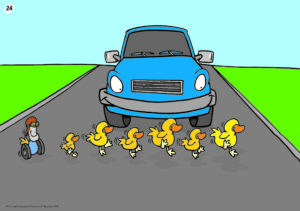

‘He chose the card that depicts a car stopped at a crossing with a line of ducklings crossing the road. In my head I’m starting to get a bit curious, but also mindful of my own interpretations of the card.

card.

‘”So, why did you chose that one.” I asked. He said, “well, this is me and my brothers and sisters (pointing to the ducklings), and this (the car) is my mum ready to mow us down”.

‘If I had jumped in with my own interpretation I would have completely missed it. For him, that card resonated in a completely different way and helped him express what he was feeling in the moment.’

When Pip isn’t in the play therapy room you’ll find her at Deakin University, investing in the next generation of Masters of Child Play Therapy graduates—teaching, supervising placements, and guiding them to become passionate advocates for the language of play as a way for children to share their stories.

She’s passionate about promoting play therapy as a valid and vital intervention in mental health support for children.

‘We shouldn’t always be turning to verbal forms of interventions for children, when we can communicate with them in their natural language. Play.’

by John Holton