Every New Year’s Eve, millions of people make resolutions related to losing weight or changing their body shape. In fact, losing weight is one of the most common new year’s resolutions, along with eating more healthily and getting fitter (which are often alternate ways of saying you want to lose weight or change your body shape).

Most of us consciously know that changing our body shape or weight isn’t as meaningful or life affirming as doing things like connecting with family and friends, finding more balance, learning a new skill, exploring the world, being grateful for what we have, getting out in nature, or being more creative. But resolutions about weight and body shape still appear at the top of many people’s list every year.

So, how does this cultural obsession with changing our body shape impact on our mental health, and on the mental health of the people we work with?

what is ‘diet culture’?

The Butterfly Foundation defines ‘diet culture’ as:

‘… a set of beliefs that promote weight loss and equate it with a person’s health, success and self-worth. It perpetuates the understanding that thinness is the ‘correct’ body size to maintain and a person is ‘morally bad’ if they gain weight or live in a larger body. Diet culture conditions a mindset that there is a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ way to eat. It encourages unhealthy practices around food, exercise and eating to achieve a desirable physical appearance.’

Diet culture draws its legitimacy from the fact that obesity can contribute negatively to a range of health issues, including diabetes, heart disease and some cancers. While these are genuine health concerns, dieting as a solution nearly always fails. Despite the research that says up to 95% of diets don’t work, with most people only losing an insignificant amount of weight, and nearly everyone gaining it back after two years, many of us continue to spend money and time on dieting. If any other medical or health intervention had such a high failure rate, we would have thrown it out years ago.

what is the problem with being caught in a ‘diet culture’?

Diet culture associates thinness with health and attaches moral virtue to particular body shapes. It encourages us to spend large amounts of time, energy, and money on diet products, by attaching a sense of shame to particular types of bodies.

Being caught in the diet cycle also contributes to a negative relationship with food (which should be one of our pleasures in life). It reduces our confidence; drains us of mental and emotional energy (which could be directed to more positive, productive and meaningful endeavors); increases anxious food-related thoughts or ‘food noise’; and often leaves us with lifelong yoyo cycles involving deprivation and overeating. As the Butterfly Foundation states, diet culture can ‘generate disturbed relationships with food, the mind and body’.

We also know that the diet industry and mass media are invested in making us feel bad about ourselves so that they can sell us more diets and diet products (the diet industry is one of the most lucrative in the world, along with the fast food industry). These highly profitable industries need us to look in the mirror and not like what we see. They also want us to believe that not having the ‘ideal’ body shape is our fault.

We live in a world where our food environment is dominated by processed foods. As Forbes magazine notes, ‘In industrialised countries, over 50% of calories come from ultra-processed foods’. This, combined with our increasingly sedentary work environments, doesn’t help us to build and maintain good health. So, we end up in cycles of dieting. This is ideal for the diet industry because they know we’ll keep coming back for more—the latest diet fad, the newest ‘research-informed’ diet or health kick.

We can choose to be part of this destructive culture, or we can choose to turn away and find more hopeful, life-affirming and healthy ways of looking after ourselves.

how does our focus on body shape impact on our mental health?

Activist, educator, and 2023 Australian of the Year, Taryn Brumfitt writes,

‘In research published in 2015, researchers found that people who report being judged or criticised because of their weight are the ones who experience the most deterioration in their health, are more than twice as likely to experience mental health concerns like anxiety and depression, and have a 60% increased chance of mortality, regardless of what their weight is.’

In Taryn’s award-winning 2016 documentary, Embrace, one of the most striking scenes is when she interviews people on the street and asks them to describe their body. Person after person, mostly women, describe their body as ‘disgusting’.

Hidden, shaming thoughts like these are something many people experience. The problem is, this negative self-talk can extend into other parts of life and may undermine our sense of wellbeing, confidence and capacity to act in the world.

diet culture, disordered eating and eating disorders

While not everyone who goes on a diet will develop an eating disorder, evidence shows that dieting is nearly always a pre-cursor for people developing an eating disorder.

As the Butterfly Foundation notes,

- Diet culture triggers disordered eating, weight-loss dieting and body dissatisfaction, which are all risk factors for the development of an eating disorder.

- Young people who diet moderately are six times more likely to develop an eating disorder; those who are severe dieters have an 18-fold risk.

- People who follow disordered eating patterns or dieting behaviours may deliberately remove themselves from social activities that involve eating. This can drive loneliness and low self-esteem.

- For those in recovery, diet culture can exacerbate an eating disorder and may make full recovery difficult.

As young people and children head back to school, and many people head back to work, anxieties about looks and body image are often heightened.

It’s not just young people who experience disordered eating. Many people of all ages and genders have carried disordered eating patterns and a distorted body image with them for years, sometime decades.

By accepting diet culture, and perpetuating it, we may be unwittingly encouraging children, young people, families, communities, and our co-workers, to see this culture as safe and ‘okay’.

body image is not just personal, it’s political

We often think our relationship to our body is just a personal thing, which is why we may not see it as a cultural construct or a political issue. This can happen for a number of reasons.

Often, we carry shame about our bodies, and with shame comes silence and secrecy, so we don’t connect with others. We may also have internalised widespread, largely unchallenged, social messages that we are lazy or weak for not fitting the current ideal, leading us to blame and judge ourselves and see our shape as a personal failing.

As a consequence, we may not see diet culture as something we need to talk to clients or students about—we see it as personal, rather than systemic. Unless they mention it themselves or have a clear eating disorder, we are unlikely to ask them about their body image or relationship with food.

The Body Positive Movement, which started in the 1980s, has always talked about body image as political:

‘Body Positivity can also be much more than battling a low self-esteem day. It can question capitalism, challenge patriarchy, and ask us to examine whether our ideas about bodies are fatphobic, sexist, racist, or ableist.’

In terms of feminism and women’s empowerment—or disempowerment—by focusing our attention on women’s body shapes, we neglect to focus on their intelligence, creativity, ingenuity, strengths, values, and vision. We tell women they can only be valuable if they look a certain way. This is a common strategy of oppression in patriarchal structures and systems.

Women may internalise these ideas and undervalue their skills, personal qualities and achievements (this is increasingly happening to men and people of other genders too). We may also perpetuate these ideas and impose them on the women and girls around us, consciously or unconsciously. For people who don’t fit neatly into binary gender stereotypes, the impact of expectations around ideal body shapes can be even more profound.

If we have a body type that is influenced or shaped by our ethnicity, culture, or genetics, and if that body doesn’t fit the ideal of the day (ideals of beauty are always changing—you just need to look at Renaissance paintings ), then we may be excluded or undervalued, based on the way we look. If people are differently abled, they may not see their body shape represented in media and other forums at all. This can lead people to be vulnerable to the messages and influence of diet culture.

Poverty, food security and food deserts can also impact on a person’s body shape. In low socio-economic areas, remote locations and increasingly in the new suburbs of sprawling cities, access to fresh, healthy foods can be limited. Highly processed foods generally have a longer shelf life so are often much more readily available in these communities. This connects body shape to economics and geographical location. If you are working with people experiencing poverty, looking at access to food as a structural or political issue may provide a different perspective on body shape, health and food choices. This alternate perspective can be used to reshape the stories clients or young people tell themselves.

Body image can also be distorted by experiences of trauma. Trauma can impact on our awareness of bodily cues (interoception), like hunger and fullness. People might also use food as a source of comfort or to medicate pain. Underlying traumas, however, are unlikely to be solved by ‘diet culture’, indeed they may be exacerbated.

Judging people on their appearance, or body shape, has long been used by the powerful to undermine the voices of those with less power, whether this is in relation to gender, class, race or disability. These issues are all political, related to inclusion or exclusion, representation, voice, power, and socioeconomic inequality.

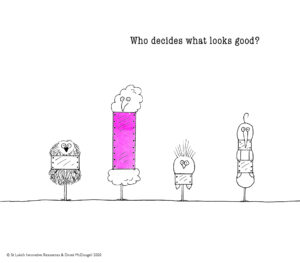

When we think about body image from this perspective, the question changes from ‘How can I lose weight or change my body shape to look better?’ to questions like — ‘Who is deciding what an ‘ideal’ body looks like?’ — ‘Where does the decision-making ‘power’ reside when it comes to the distribution of healthy food?’ — ‘If these are social justice issues, how can I advocate for more transparency and inclusion?’

what can we do to challenge unhelpful ideas about body image?

We can start by examining our own relationship to food, body image, diet culture. We might ask ourselves:

- What aspects of diet culture have we internalised that we model, consciously or unconsciously, with our children, students, clients or colleagues?

- What messages might we be sending them about what it means to be healthy and confident in the world?

- Do we talk about our latest diet or share dieting tips as a way of building rapport and connection with others? What if we shared positive stories about how we use our bodies instead (a hike where we got a great view, dancing with our kids, having a belly laugh with friends, or sharing a great meal)?

- How do we talk to ourselves about food, our body shape, health and exercise? Is our inner voice nurturing and encouraging or critical and undermining?

- What media do we consume that might be embedding unhealthy ideas about body shape? (You can tell if the social media you’re consuming is unhealthy if you come away feeling worthless, anxious about the way you look, un-lovable, helpless, or powerless. Healthy sources of media should leave you feeling empowered, hopeful, inspired, energised and capable.)

- How might we be sending messages to others, verbal or nonverbal, about how they look, or should look?

- What disempowering cultural messages might we be perpetuating without knowing it?

We might also explore some of the alternate approaches to diet culture, like those coming out of the various body positive movements, including body neutral or body appreciation perspectives. These movements or approaches tend to focus more on what our bodies can do rather than how they look.

In an article on the body positivity movement, The Conversation makes the point:

‘We are all more than just our bodies. We are complex beings with a range of emotions and feelings about our bodies. And because body neutrality de-emphasises the focus on appearance, it allows us to better appreciate all the things our bodies are able to do. Being grateful for being able to do the hobbies you love or appreciating your body for what it’s capable of doing are both examples of body neutrality.’

Food and eating have always been some of the great pleasures in life. We connect with family, friends and community through food. We share our culture and identify with food. We show love and care with food.

If we can find our way back to having a warm, respectful, joyous relationship with food and our bodies, our lives are likely to be more balanced, healthy and connected. We are also more likely to have an inner voice that is kind, nurturing, and curious rather than judgmental, allowing us to focus on much more important things than our appearance.

By Dr. Sue King-Smith

All card images in this article are from the Eating disorders & other shadowy companions cards

Thank you Dr. Sue for this wonderful paper to read. I’m a school chaplain at primary school. I haven’t come across student issues of diet and body image, however it probably sits in their young hearts.

I appreciated reading about my talk and language …”What we can do to challenge unhelpful ideas about body image”.

* Renaissance paintings 🙂